CRITICAL ESSAY

In contrast to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) trope which is the modern-day TV and film adaptation of the “nurturing woman or the muse,” of the 20th century (Rodriquez 121), the ‘It’ Girl in Distress is characterized as a parasite. She absorbs the energy of those around her rather than being a source of light and energy in the life of a male protagonist, whose miserable life she exists solely to improve. Where the MPDG’s personality is never developed outside of her relationship to a man (Rodriguez 171), her distressed counterpart has her traumatic past presented to viewers, but never fully explored past the notion that it made her the mysterious, alluring, and slightly eccentric character. In this essay, the appeal of the trope to different segments of the audience will be considered, as well as its impact on them, which is mostly harmful.

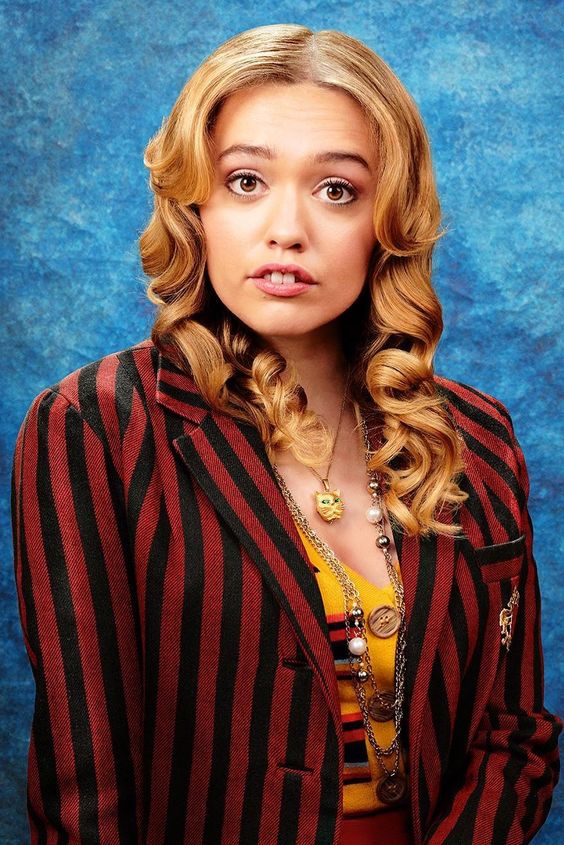

This trope is shown in several Netflix originals, including Firefly Lane where the protagonist, Tully Hart is a 43-year-old successful and attractive woman who repeatedly gets flashbacks of her mother being neglectful during her childhood, and of the sexual assault she endured at 16. Throughout the serial, she was never shown confronting her past productively or attempting any inner work. Instead, she engages in excessive drinking, and is averse to developing emotional relationships with men, limiting her interactions with them to one-night stands as they yearn to get to know her. Tully is clearly portrayed as a miserable character, but her misery is romanticized, with one flashback scene showing her coworker Johnny watching her dance longingly while asserting that he knows how terribly sad she is. Another Netflix original where this trope was used is Cable Girls, in which Lydia, who is also the protagonist, is shown as having had a traumatic past as a teenaged girl when she worked in a brothel and was subjected to harassment and assault by many older men. Her trauma also remains unexplored but shows up in intrusive flashbacks. Meanwhile, Lydia fulfils the femme fatale trope in her present-day scenes by being the serial’s primary object of desire and ‘tricking,’ men into ruining aspects of their own lives to be with her.

While these examples may fulfil the reasoning conveyed by Nussbaum, which is that survivors of sexual assault may find “something validating,” about seeing their experience portrayed on Netflix (2), or that all women may encounter a “strange therapeutic quality,” (Nussbaum 2) from seeing this fear in serials. It is necessary to challenge such interpretations of the trauma-loaded stories currently popular on Netflix, and to avoid internalizing them, because the “trauma trope,” (Beam 2) may have become more focused on the shock value that works so well within the aim of commodifying the narratives of victims of trauma. When considering the goals of Netflix and television producers under capitalism more broadly, it is reasonable to infer that the viewer retention attained because of shock value is prioritized over creating cathartic, relatable narratives for survivors to seek comfort in, or just accurately representative narratives that would promote the recognition and eventual understanding of rape culture and its effects on victims. Such narratives would require more in-depth explorations of trauma and more deliberate writing.

On one hand, Netflix did show one example of a sensitive and non-romanticized representation of sexual trauma, through a subplot revolving around the character of Amy in Sex Education, as she navigates the aftermath of having been assaulted on the bus, her recovery journey is the focus of her story, and the scenes where she gets triggered and her trauma responses are shown on screen, conveying that healing is not linear, offer a sense of catharsis to survivors in the audience. Amy’s realistic trauma responses and healthy approach to accepting and dealing with the incident rather than suppressing it, can simultaneously make survivors feel seen and encourage them to seek assistance while being gentle with themselves throughout the process, acknowledging that setbacks are a natural part of it. Therefore, appealing to them as viewers through its provision of some relief and relatability This subplot is in contrast with the Netflix narratives discussed above, since as opposed to romanticizing trauma, it portrays a journey of unpacking it. Interestingly, the two starkly different portrayals may retain the same viewership of survivors who long to disconnect from the reality of their own trauma by focusing on that of fictional characters instead, whether they are realistic or romanticized.

As for other viewers, namely those who do not relate to the traumatic experiences that this female character trope has endured, the appeal may stem not only from addiction to the shock factor, but also the perverse way in which watching so much television where traumatizing events including sexual assault, are openly portrayed on the screen, enables them to become desensitized to it (Nussbaum 2). Becoming desensitized perpetuates a cycle where viewers continue to support “trauma fetishization and commodification,” (Beam 5) and allows them to continue viewing these Netflix originals uncritically. This is not a new phenomenon and stems from generations of this trope’s predecessors, as Claire Solomon notes in ‘Anarcho-Feminist Melodrama and the Manic Pixie Dream Girl,’ media tropes that reduce women to a set of features intended to be appealing belong to an ever-developing “master narrative,” of “unstable femininity,” (2).

The appeal of the “It” Girl in Distress trope to male audiences can be attributed to a patriarchal savior complex, it is comfortable for men to see ‘damsels in distress,’ depicted in media as it enables them to “cling for security and safety to the underlying assumptions of patriarchal ideology,” (hooks 126) without having to interrogate the ways in which they may subconsciously view women as needing men in their lives in order to be happy and stable. This analysis is particularly relevant to this trope because the female characters who fit it like Annalise Keating, Tully Hart, and Lydia Aguilar are seldom in stable romantic relationships with men. Therefore, an additional harmful impact of the trope is that it reinforces patriarchal ideas about single women lacking the ability to maintain stability on their own. Another appeal that is specific to male audiences is created through how this trope caters to the male gaze. Although it shows the female characters struggling in many ways, this rarely, if ever, interferes with her beauty or reveals the process of maintaining it, Oullette refers to this process as “the manufacture of the female object,” (170) and it is absent in these serials which otherwise depict deeply personal and intimate scenes, therefore protecting the “fantasy,” that male audiences are drawn to in depictions of women in media.

In conclusion, the “It” Girl in Distress trope is not a feminist development in the realm of women’s portrayal on television. As the producers of Netflix originals are mainly focused on viewer retention rather than political messaging, sensitive topics are depicted rather hastily, which is harmful to real victims of the topics being explored, and in the grand scheme of things contributes to upholding patriarchal ideology. All in all, the trope’s success can be attributed to its shock value, its catering to the male gaze, and its misplaced relatability.